Anger In Children

Anger is normal! Yes, that’s right, anger is an ordinary and meaningful part of the human emotional experience. Most parents will face stamping feat, screaming (often public) tantrums, flying toy missiles and wall graffiti at some point. But for some children, anger can present in much more concerning behaviours, such as aggression with threats of violence, destruction of property and assault. Although it is often hard to see, all anger has a purpose,. Understanding this purpose of a childs anger is the first step toward behaviour change.

One important step in understanding anger is learning how to break it down into components. The emotional component (how the child feels in their body) is what we call anger. The behavioural component (what the child does to express their anger) is what we call aggression when these actions are hurtful. It is really important as a parent and educator to understand this difference. A child can feel intense anger, but choose to express it appropriately. For example, they feel angry, but do not use aggression.

It is also important to know that the child’s identity is neither the anger or the aggression! How they feel and act are separate to who they are as a person. Try to avoid phrases such as ‘just an angry kid’…as these lead your child to believe that anger is a part of who they are rather than an emotional state that is changeable with the right strategies.

As adults, we can help kids by not treating anger as something that is inconvenient, wrong, or ‘bad’. Anger has established a name for itself as a negative emotion, largely because it feels uncomfortable in the body. For example, feeling hot and tense, agitated, shaky, or fast heart rate and breathing. Despite this, anger is an important human emotion that helps us by communicating information. As a parent or educator we can assist children greatly by helping them to recognise the signs of anger in their body, to cope with how they feel, and to encourage them to express their anger in an appropriate behaviour. We can also learn about why they experienced the purpose that the anger served. This is called helping a child to gain emotional intelligence.

What is the purpose of anger?

Anger can arise for many reasons. The interesting thing about anger is that it usually serves a purpose and assists the child in some way. Here are some of the reasons behind childhood anger:

– ANGER AS FEAR: Anger can help children by preparing them to take action against a threat (real or imagined!). The anger response can occur as part of the body’s “fight or flight” response if a child senses danger. Their body provides an intense and natural self-protection reaction to a situation. These intense and building feelings can lead to aggressive reactions.

– In the brain, a cocktail of chemicals triggers an energy rush in the child, which can lead VERY quickly to an aggressive reaction. If a child feels this way frequently, long term changes can occur. For example, the child becomes ‘action-ready’ for hours and sometimes even days. Over this time, anger outbursts can occur from even minor annoyances, as the child’s body is already primed and ready to react. Many children have great difficulty controlling, stopping or reducing these anger reactions. They often feel remorseful after their behaviour and cannot understand why they reacted in the way that they did.

– ANGER AS EMPATHY: Anger can help a child by outlining situations that are unfair or where the child perceives injustice. A child might feel angry when they feel that they have been unfairly treated. In this way anger can assist a child to develop something we know as empathy. Empathy in children is their capacity to understand the experience of somebody else and feel what they are feeling. We can see this behaviour in kids as young as two years old. For example, when a two year old sees another toddler become angry and kick a ball in response, they will often imitate this behaviour themself sharing the emotion and experience of anger. Empathy development is a very important stage in child development, and you can use your child’s anger to discuss their empathy and emotional development.

– ANGER AS SHAME: Anger can help by upholding a child’s sense of pride or dignity. In some cases a child may use anger as a role to avoid shame. For example, if they feel embarrassed by not understanding their lessons at school. In this scenario they may opt to be seen as the ‘naughty’ kid and act out in anger, rather than face the shame of admitting that they need help. This helps the child to maintain their positive sense of self as capable of mastering new skills. However, experiencing anger to avoid shame isn’t always helpful. Children who experience anger because their friends are teasing them, may also develop a ‘schema’ or belief that all friends are mean. Each time they enter a social group in the future this schema will be triggered and they may be over sensitive to hostility and are more likely to become angry again.

– ANGER AS COMMUNICATION: Anger can help children who do not understand their emotions to communicate to others that they need something or that they don’t feel well. Young children who have not yet learned how to differentiate between different emotional states may present all of their communication as anger. A screaming child may mean “I’m hungry”…”I’m tired”…”I need affection”…”My nappy is dirty”… or ”I’m cold”… This style of behaviour may continue in children who have developmental delays, sensory problems, or have not been able to learn about their emotions properly.

Why is anger so many different things?

The science of childhood anger indicates that when expressing anger, children often demonstrate misunderstanding about a situation. Research has shown that aggressive children make mistakes when understanding information about situations and environments that they are in. They also have a tendency to see others as ‘out to get them’ or hostile, which is known as a thinking error. These children have a habit of over-reacting to situations and feeling justified when blaming others for their actions. What’s more, these kids not only have difficulty coming up with different options to solve a problem, they also show difficulty in evaluating what solution is best.

So how can we help these kids out?

– Help them to correct/improve their thinking

– Help them to talk to an adult to gain help before reacting to a situation

– Help them to learn how to generate more solutions to their problems

– Help them to evaluate the best solution by discussing different actions and consequences

– Help them to understand and cope with the sensation of anger in their body

What type of anger is it?

There are also two types of anger that children may use. These are known as proactive anger, and reactive anger.

- – Proactive – a child with this type of anger is using their anger or aggression to achieve a goal. For example, a proactively angry child who doesn’t want to eat their vegetables might throw them in your face! Or, if they want their brothers ball they will aggressively snatch it. If the child succeeds at getting what they want, they are more likely to use aggression again because they know that it works! Their anger response may seem more driven by power and manipulation. This type of aggressive behaviour is more likely in young children. They might see others as blocking their way to achieve a goal, and experiment with using anger as means to get what they want.

- – Reactive – a child with this type of behaviour is reacting to things around them. They may seem like a child that is easily provoked or over sensitive. Their anger response will seem more driven by emotion. So, although these kids might not plan to have such reactions, reactive anger often means rejection by their friends and bullying. A lot of the time, these kids may mistakenly think that others have picked on them. Older children may use this type of anger if they feel that their self-esteem has been harmed.

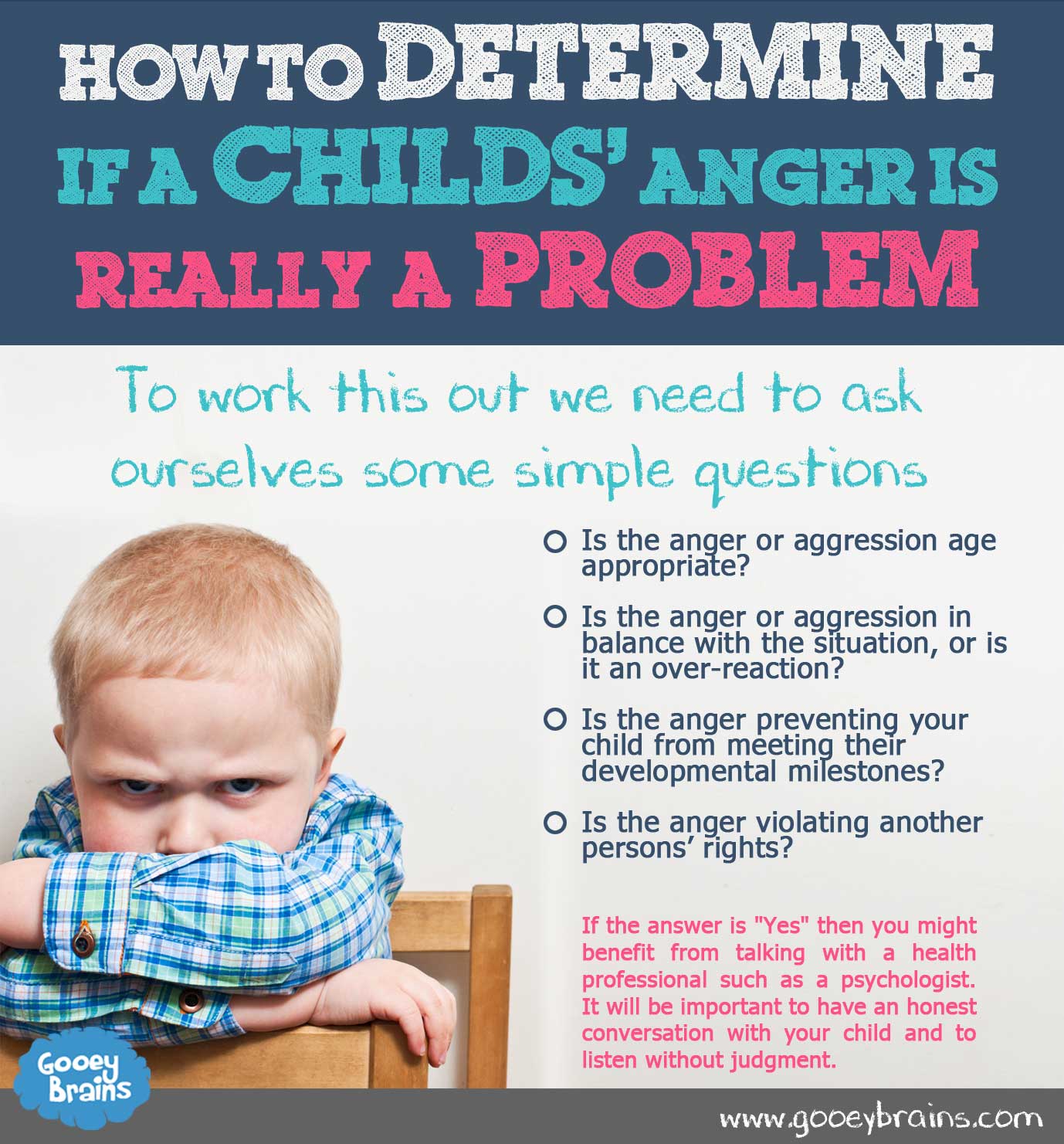

Is the anger really a problem?

To work this out we need to ask ourselves some simple questions:

- Is the anger or aggression age appropriate?

- Is the anger or aggression in balance with the situation, or is it an over-reaction?

- Is the anger preventing your child from meeting their developmental milestones?

- Is the anger violating another person’s rights?

If the answer is “Yes” then you might benefit from talking with a health professional such as a psychologist. It will be important to have an honest conversation with your child and to listen without judgment. This will help you to explore their anger and learn the purpose of their aggressive behaviours. Your child will likely need your help (or the help of another adult that they trust) to learn to cope with the feeling of anger. They may also need to learn how to plan and problem solve, and to learn alternate behaviours to express their anger. A health professional can assist you to have important conversations and provide ideas on how to solve problems as a family.

When anger is a problem.

Problem anger in children is important. Research has linked early aggression to things such as low achievement and substance abuse in adulthood (Brook & Newcomb, 1995). These kids may be at risk of mental health problems and behavioural disorders later in life (APA, 1994). Anger is also a problem when it interferes with a child engaging in education or maintaining a friendship group.

Monkey See Monkey Do

Many people ask “where does a child learn their aggressive behaviours?” Children say and do what they see and hear around them. Children model the behaviours of their parents, siblings, school mates and even TV stars. Not only do children watch and copy others, they also pay attention to what happens to other people when they are deciding if they will copy the behaviours. In 1961, a famous psychologist named Albert Bandura conducted a world renowned experiment that showed that children copy and model aggression demonstrated by an adult even without reward or punishment. This experiment is now known as the ‘Bobo Doll Experiment’. A series of children watched an adult behave aggressively toward an inflatable friendly clown. The children then then became more likely to show similar aggressive behaviours. They kicked it, hit it with a mallet, and threw it. They even invented new ways of hurting the clown that were not demonstrated by the adult such as shooting it or throwing darts at it. It is now widely accepted that children can learn aggression simply through observing others.

Reference Articles and Further Reading:

- Lochman, Powell, Clanton and McElroy (2006)

- Brook and Newcomb (1995)

- Tremblay, Hartup, and Archer (2005)